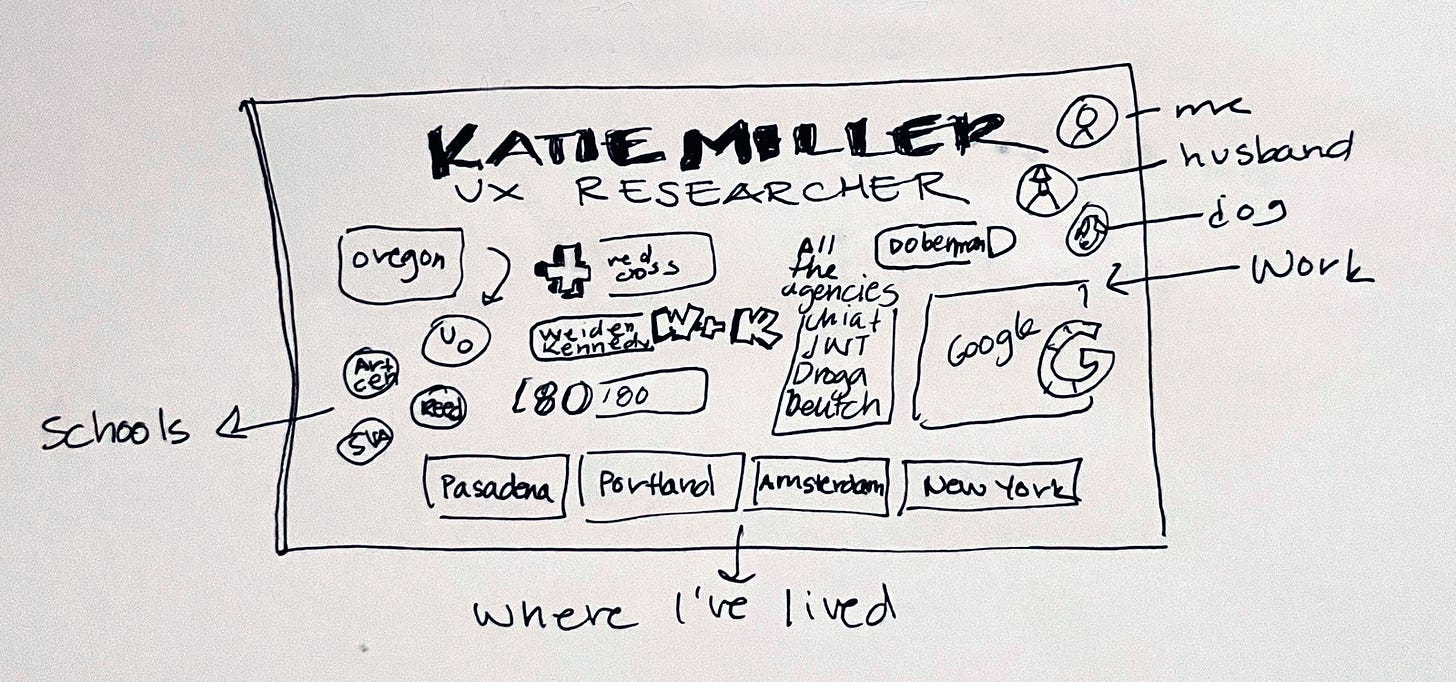

If I asked for your professional story visualized on a presentation slide, chances are you could make one in about five minutes, and it would feature some variation of this information:

your hometown

the schools you attended and degrees you earned

the most interesting or relevant jobs you’ve had

places you’ve lived

a few hobby, family, or travel photos

The visuals and tone may change depending on the audience, but by and large, it’s not hard to distill yourself down to a short story, especially after being asked to do it for every new job for decades.

And that’s what’s wrong with intro slides. You and I are so much more than our demographics; what makes us interesting is our experience.

Last summer, I gave a talk called “Bias as Superpower” to encourage new Google employees to draw from their personal experiences and find strength in the collection of circumstances that led them to become Nooglers (Google employees who’ve been full-time at the company for less than a year). This pep talk was necessary because imposter syndrome, or a sudden loss of self-confidence and the simultaneous feeling that you're about to be found out as an erroneously hired fraud, is common, almost ubiquitous, when starting a new position. Imposter syndrome seemed particularly pernicious amongst Nooglers, resulting from a sudden crash from a self-confidence pinnacle (I got a job at Google!...) to the deep doubt of not knowing how to succeed (... but what should I do now that I’m here?) It is daunting to speak up when the voices in your head are urging you to stay small until you figure out how to be, and silent until you figure out what to say. Especially as a new team member, your first contribution, your introduction, should be right, right?

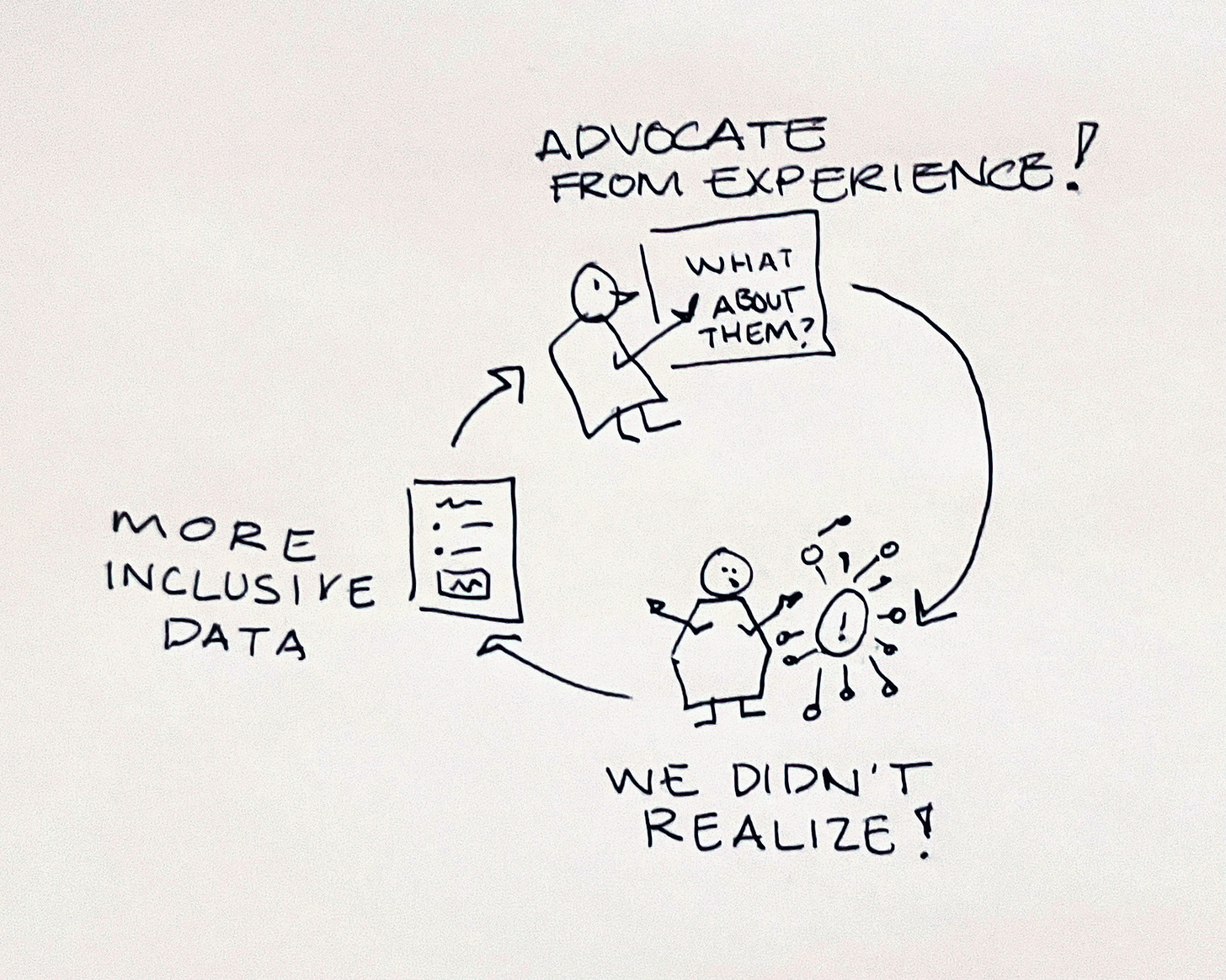

In the talk, I shared how I battled imposter syndrome by volunteering on projects and initiatives with teams other than my own. Like with anything, speaking up takes practice, and as a volunteer, I felt able to make recommendations and try new approaches without worrying about judgment from the people in charge of my performance review. With practice came confidence, and I was able to bring more of myself to projects, using my experience to make suggestions that wouldn’t necessarily occur to others. For example, when I worked with a committee to personify typical user experience researchers, I advocated for the atypical person who’d come to UX research after working in different industries and without an advanced degree—the UXR with a story like mine. When volunteering, it was easier to put my perspectives and biases forward, practicing how personal experience can be tapped to expand stakeholders' definitions of Google’s users. As my suggestions were taken and the projects benefited, I gained confidence to bring my full self back to my home team, where the cycle continued.

I've been thinking about this talk a lot lately because I'm falling into imposter syndrome again, only this time it's reversed. In January, along with 12,000 others, I received a Friday morning email from Google telling me I was laid off. We had no warning about the abrupt and impersonal “we no longer have a job for you” notice. Cuts were made at every level and every job type, regardless of tenure or performance, but I am most aware of women like me with loads of life experience who are now looking for what’s next: the next job, the next step, the next incarnation, the next right thing.

In the early weeks of unemployment, I suspect most of us start distilling our work accomplishments down to bullet points in order to update our resumes and LinkedIn profiles. But in the rush to reduce our experience down to intro slide-levels, all in service to bots, keywords, and efficiency bias, are we in danger of betraying ourselves? How do we push against the pressure to make ourselves small, to become imposters, in order to compete? At what point do we refuse to make ourselves generic again?